Research - (2022) Volume 10, Issue 1

Determinants of market orientation and market participation: Agricultural commercialization in central and North Gondar rural Ethiopia

Tigabu Dagnew Koye1*, Abebe Birara Dessie1 and Tegegne Debas Malede22Rural Development and Agricultural Extension, College of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences, University of Gondar, Gondar, Ethiopia

Received: 01-Mar-2022, Manuscript No. AAFSF-22-55833; Editor assigned: 04-Mar-2022, Pre QC No. AAFSF-22-55833 (PQ); Reviewed: 18-Mar-2022, QC No. AAFSF-22-55833; Revised: 25-Mar-2022, Manuscript No. AAFSF-22-55833 (R); Published: 04-Apr-2022, DOI: 10.51268/2736-1799.22.10.71

Abstract

In Ethiopia, agricultural transformation is faced with many challenges such as poor infrastructure especially in a rural area where huge agricultural activities are carried out, poor institutional services, lack of awareness of farmers on the value addition of goods, and so on. To fill this knowledge gap, this study was aimed at the determinants of market orientation and market participation in Central and North Gondar Rural Ethiopia separately. The data have collected from a sample of 344 households selected using multistage purposive and random sampling techniques. Seemingly Unrelated Regression (SUR) and Tobit regression models were employed. The SUR model estimation indicated adult equivalent, chemical fertilizer users and Tropical Livestock Unit (TLU) affect both market-oriented cash and stable crops positively, while child dependency ratio, cultivated land, the distance to the market, and road affect both market-oriented cash and stable crops negatively. Level of education (grading), and irrigation users affect market-oriented cash and stable crops positively, respectively. The empirical results of the Tobit model show that cultivated land, land allocated to staples, off/non-farm income, and irrigation user affect crop commercialization positively. Based on the findings, the study suggests that farmers should keep going to employ additional off-farm income activities, improve rural-urban roads, employ agricultural intensification, and the government should be supplied chemical fertilizer in sufficient amounts and on time at a reasonable price to improve farmers’ crop production.

Keywords

Capsaicinoid, Capsicum annuum, Nitisoil.

Introduction

Smallholder farmers in Africa have a large share of the arable land; it is not feasible to envisage agricultural transformation without considering them (Holden TS et al., 2014). From the view of most development agencies, research centers, and governments, the transformation targeting increased productivity among smallholders would be the best way to enhance rural income in the short and medium-term (Larson et al., 2014).

Some researchers also argue that the transformation of smallholder farmers should be the dominant approach for agricultural-led growth in Africa (De Janvry et al., 2010). Others indicate that improving the production systems of the smallholders as well as their access to markets is becoming a strategy for rural development and poverty reduction (Fischer E et al., 2010). Additionally, when focusing on commercialization, smallholder market participation has been recognized as crucial for the transformation to significantly bring the expected growth (Jagwe et al., 2010).

In Sub-Sahara Africa (SSA) the majority of the population lives in rural areas where poverty and deprivation are severe. It is estimated that about 70% of the rural poor in SSA depend on agriculture for their livelihood directly or indirectly (IFAD, 2011). Therefore, agricultural transformation is crucial for poverty reduction and improved food security in Sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries, as the agricultural sector is characterized by mainly small-scale, low productivity, low external input usage, and family labor-oriented enterprises World Bank Poverty reduction strategies focusing on agriculture directly raise farm incomes by increasing marketable output and indirectly through generating employment as agriculture is labour-intensive. The agricultural sector also has linkages with other sectors such as processing industries and factor markets (Pender et al., 2007).

The Ethiopian economy is highly dependent on agricultural activities. The agricultural sector contributes 42.7% of GDP, providing employment opportunities for 80% of the total population, generates about 70% of the foreign exchange earnings of the country, and supplies over 70% of raw materials for domestic industries. However, having such great significance in countries’ economies, commercialization of agricultural products until recently has been low. Commercialization of the agricultural sector is faced with many challenges such as poor infrastructure especially in a rural area where huge agricultural activities are carried out, where there are poor institutional services, lack of awareness of farmers on value addition of goods, and so on.

Commercialization in agriculture refers to the progressive shift from household production for auto consumption to production for sale in the market. This shift entails that production and input decisions are based on profit maximization, reinforcing vertical linkages between input and output markets (Olwande et al., 2015). Commercializing smallholder agriculture is seen as a means to bring the welfare benefits of market-based exchange economies to this group and is central to an inclusive development process (Arias et al., 2013). Smallholder commercialization is seen as preferable to relying on migration to urban centers where employment growth remains low. Focusing on smallholders also promises to deliver more equitable rural economic growth than commercialization strategies that focus on large farms, with small farms typically employing more labour per unit area compared to large farms, and small-farm household expenditure patterns bring greater benefits to local economies (Hazell et al., 2010).

Agricultural commercialization refers to the process of increasing the proportion of agricultural production that is sold by farmers. Commercialization of agriculture as a characteristic of agricultural change is more than whether or not a cash crop is present to a certain extent in a production system. It can take many different forms by either occurring on the output side of production with increased marketed surplus or occurring on the input side with increased use of purchased inputs. Commercialization is the outcome of a simultaneous decision-making behaviour of farm households in production and marketing von.

Moreover, the commercial transformation of subsistence agriculture is a crucial policy choice in economic growth and development for many developing countries like Ethiopia. Agricultural commercialization brings about sustainable food security and welfare and enhances vertical and horizontal market linkages. Agricultural commercialization and increased food production is the cornerstone for increasing food security. Smallholder farmers are often good at allocating resources efficiently, therefore those commercializing will contribute largely to economic growth and food security. This will create employment opportunities which eventually enable people to afford nutritious food for a healthy life.

The transformation has generally been considered as shifting from subsistence farming, which is characterized by low productivity to a market-oriented production system (Olwande et al., 2015). It is accompanied by using improved inputs, which are designed to lead to higher agricultural production for food self-sufficiency and commercialization. With increased commercialization, agricultural transformation is then seen as an effective way to boost household income and stimulate pro-poor growth (Diao et al., 2010). In addition, transformation is intended to benefit the rural landless through wage labour creation and food availability.

An increase in market participation by the small householders in Ethiopia is an important means of transforming from subsistence farming into commercial farming and it is documented in the current development strategy of the country (MoFED et al., 2010). The transition from subsistence to commercial agriculture has long been considered to be a crucial strategy towards the agrarian transformation of low-income economies and a means of ensuring food security, enhancing nutrition and incomes. The transition from low productivity and semi-subsistence agriculture to high productivity and commercialized agriculture has played a central role in the development of agricultural economics (Zanello, 2011).

To achieve food security, the commercial transformation of subsistence agriculture is an indispensable pathway towards economic growth and development for many agriculture-dependent developing countries. It is evidenced that policy, technological, organizational, and institutional interventions aimed at promoting the commercial transformation of subsistence agriculture should improve the market orientation of smallholders at the production level, and facilitate market entry and participation of households in output and input markets. The dynamics and feasibility of smallholder commercialization in improving the food security situation is an important policy issue. The commercial behaviour of smallholders and the commercialization scale at which they are operating is also a critical research question to be addressed since smallholder commercialization policies are usually designed under such conditions. Various studies on smallholder commercialization generally suggest that there is a very low scale of commercialization in Ethiopian agriculture with differentiated factors determining the market orientation and commercialization decisions of rural households (Moti et al., 2008; Adane, 2009; Mamo et al., 2009; Bedaso et al., 2012).

The literature on the commercialization of smallholders makes a clear conceptual distinction between market orientation and the market participation of smallholders. As a result, most of the analysis of the determinants of smallholder commercialization is based on the analysis of the determinants of output market participation (Jaleta et al., 2009 and Otieno et al., 2009). However, analysis of the determinants of market orientation and market participation separately would be useful in guiding the type of interventions needed at production and marketing levels to facilitate commercial transformation. Improvement in market orientation and participation is therefore needed to link smallholder farmers to markets to have a suitable market for agricultural products as well as to receive a boost for income generation. This paper, therefore, makes the distinction between market orientation and market participation and attempts to analyse the determinants of each separately.

Research Methodology

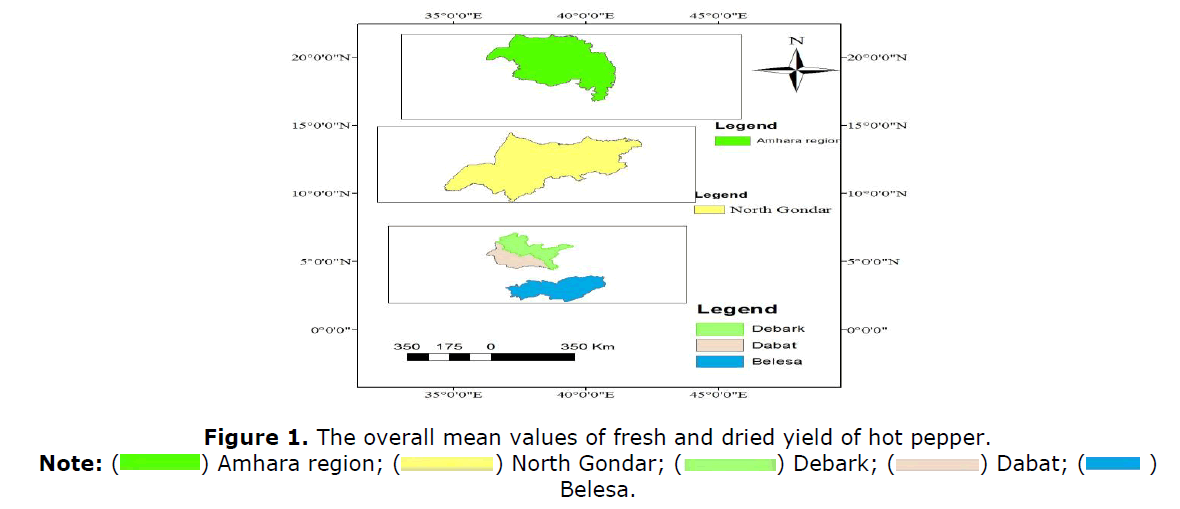

Description of the study area

The study was conducted in Central and North Gondar Districts (Debark from North Gondar; West Belesa and Wogera from Central Gondar). The weather conditions of these Districts are characterized by Dega, Woiyna Dega, and kola there are mixed farming systems (i.e. livestock rearing and crop productions). The crop production systems are characterized by rain-fed and irrigation. According to the zone agriculture department, the main staple food includes sorghum, maize, and potato. Other food crops include barley, wheat, Teff, and pulses. Cash crops like malt barley, lentil, haricot bean, and sesame. Onion, tomato, potato, and others are some of the vegetables produced in irrigation fed (North and central Gondar Zone agriculture office, 2018) (Figure 1).

Data types, sources, and methods of data collection

This research was primarily based on primary data through a cross-sectional survey during the 2018/19 production season. The research was adopted a cross-sectional survey as opposed to a longitudinal survey since the latter requires taking a repeated measurement continuously that has cost and time implications. Hence, it becomes difficult to employ such kind of design in research of this type. However, a cross-sectional survey requires one-time data collection and analysis which in turn is time-saving and cost-effective (Kothari, 2004). Therefore, this study was designed to undertake a cross-sectional survey. The cross-sectional survey was conducted using a semi-structured questionnaire.

Sampling technique and sample size

A multi-stage sampling technique was employed when selecting sample respondents. Central Gondar and North Gondar administrative zones of the Amhara Region were selected purposively from the two agro-ecologies. Since two agro-ecologies are expected for their heterogeneity in terms of their commercialization situations, a two-stage stratified random sampling technique was employed. In the first stage of sampling, districts will be stratified according to their agroecology such as highland and mid attitude.

To obtain representative sample households from the agroecology, two districts West Belesa and Wogera from Central Gondar and Debark from North Gondar were selected purposively. In the second stage, five Kebele Administrations (KAs) in West Belesa and; four KAs from Wogera and Debark (total eight KAs) were randomly selected. Finally, a total of 344 rural households were randomly sampled from 13 KAs proportionate to the number of households in each District.

Methods of data analysis

Descriptive statistics (percent and mean) and econometric analysis were used to analyze data.

• Market Orientation and Commercialization

• Market Orientation Index (MOI)

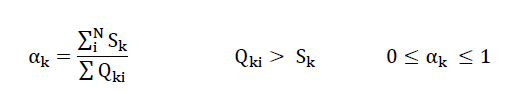

The household’s decisions as to which crop, categories to produce are assumed to be interdependent. The decision to produce one type of crop is at the expense of the production of the other crop for the fact that resources, particularly land, labor, and capital, are limited. We define that a smallholder is market-oriented if its production plan follows market signals and produces more marketable commodities. Under a semi-commercial system, where both market and home consumption are playing a central role in production decisions, all crops produced by a household may not be marketable in the same proportion. Thus, households could differ in their market orientation depending on their resource allocation (land, labour, and capital) to the more marketable commodities. Marketability of cereal crops will be computed at the district level since districts are the closest representatives of the farming systems included in the study. Hence, based on the proportion of total amount sold to total production at the district level, a crop-specific marketability index (αk) is computed for each crop produced at the district level as follow

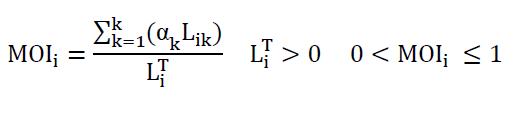

Where αk is the proportion of crop k sold (Ski) to the total amount produced (Qki) aggregated over the total sample households in a district. αk takes a value between 0 and 1, inclusive. Crops mainly produced for markets usually have αk values closer to 1. Once the crop-specific marketability index is computed, the household’s market orientation index in land allocation (MOIi) is computed from the land allocation pattern of the household weighted by the marketability index of each crop (αk) derived from the above as follows..

Where MOI is the market orientation index of household i, Lik is the amount of land allocated to crop k, and Li is the total cropland operated by household i. The higher proportion of land a household allocates to the more marketable crops, the more the household is market-oriented. The equation for households’ market orientation scale between staples and cash crops will be assumed to have some correlation. To account for this, the equations for households’ market orientation of staples and cash crops will be estimated by a two-equation Seemingly Unrelated Regression (SUR) model.

moisti=X1β1+εi1

moici=X2β2+εi2

Where: moist and moic are market orientation scales of staples and cash crops of households, respectively.

Tobit regression model

The determinants of the level of market participation were estimated using the Tobit model. The model is explicitly expressed as:

Zi=α0+αiSi+εi

Where: Zi=sales volume in percentage; α0= intercept; αi= parameters; Si=Variables that determine market participation, and εi= error term

Results and Discussion

Market orientation estimation using SUR model

Table 1 below presents coefficient estimates of the Seemingly Unrelated Regression (SUR) model for households’ market orientation. This study tested the null hypothesis that error terms for households’ market orientation are not related. The Breusch-Pagan test rejects the null hypothesis of independence between the market orientation index of cash crops and the market orientation index of stables crops residual series at the 1% level of significance. The test empirically confirms that it is appropriate to estimate the simultaneous equations of the market orientation index of cash crops and the market orientation index of stables crops using the SUR model.

| Dependent variables | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variables | Market orientation index of cash crops | Market orientation index of stables crops | ||||

| Coef. | Z | P>|Z| | Coef. | Z | P>|Z| | |

| Cons | 24.77 | 0.36 | 0.719 | 14.72 | 0.25 | 0.8 |

| Age | -0.29 | -0.69 | 0.488 | -0.4 | -1.13 | 0.26 |

| DeprC | -0.15* | -3.19 | 0.001 | -0.11* | -2.79 | 0.005 |

| Adeq | 8.34* | 2.73 | 0.006 | 5.21** | 2.02 | 0.043 |

| Grade | 3.62** | 2.55 | 0.011 | 1.4 | 1.17 | 0.241 |

| Traing | 8.5 | 0.56 | 0.574 | 17.99 | 1.41 | 0.157 |

| Land | -11.59*** | -1.74 | 0.081 | -13.97** | -2.5 | 0.012 |

| Irrig | 13.12 | 1.35 | 0.176 | 15.89*** | 1.95 | 0.052 |

| Fert | 56.69* | 3.65 | 0 | 45.05* | 3.45 | 0.001 |

| Govp | -14.64 | -0.71 | 0.481 | -11.92 | -0.68 | 0.495 |

| Hyvc | -7.25 | -0.63 | 0.532 | -0.93 | -0.1 | 0.924 |

| Extcont | 0.26 | 0.72 | 0.471 | 0.3 | 0.98 | 0.326 |

| Oxq | -2.4 | -0.31 | 0.756 | -4.04 | -0.62 | 0.534 |

| TLU | 4.52*** | 1.96 | 0.05 | 4.67** | 2.4 | 0.016 |

| Market | -1.23* | -2.9 | 0.004 | -0.95* | -2.66 | 0.008 |

| Road | -0.57* | -2.8 | 0.005 | -0.51* | -2.94 | 0.003 |

| Lncreditq | 2.56 | 0.42 | 0.677 | 4.95 | 0.96 | 0.339 |

| Lnoncom | 7.45 | 1.39 | 0.164 | 5.3 | 1.18 | 0.239 |

| R2 | 0.6251 | 0.6172 | ||||

| Chi2 | 73.35 | 70.94 | ||||

| Breusch-Pagan test of independence: chi2(1)=37.113 | ||||||

Note: Source: Computed from Field Survey Data, 2019/20; *, ** and *** are significant at 1%, 5% and 10%, respectively.

The child dependency ratio detracts from household market orientation both market orientation indexes of cash and stables crops due to its effect on increasing household domestic consumption needs, as expected. A higher dependency ratio is likely to reduce productivity growth. Growth in the non-productive population will diminish productive capacity and could lead to lesser market orientation indexes of cash and stables crops. As proportions of child dependency ratio increased by 1%, market-oriented cash and stables crops declined by 0.15% and 0.11%, respectively.

Family size (adult equivalent): Labor availability was found to be a positive and significant effect on both market orientation indexes of cash and stables crops. This indicates that large labor availability supplies more labor that can be well utilized at a relatively better price. As the active labor force increases by 1%, market orientation indexes of cash and stables crops increases by 8.34% and 5.21%, respectively.

For the improvements in farm household agricultural commercialization, the role of farm technologies, like the use of fertilizer, play an important role. The use of fertilizer adoption was both market orientation indexes of cash and stables crops than non-users. It is positive and statistically significant on both market orientation indexes of cash and stables crops at 1% probability level. The role of fertilizer adoption was facilitating rural transformation as higher production into surplus products and greater ability to integrate with the output market. As hypothesized, if the use of fertilizer adoption of farm household increased by 1% unit, market-oriented on cash and stables crops found to be increased by 56.69% and 45.05% units, respectively. Thus, fertilizer adopters are enhancing both market orientation indexes of cash and stables crops than non-users.

The estimated coefficient associated with livestock holding (TLU) is positive and statistically significant on both market orientation indexes of cash and stables crops at 10% and 5% probability levels, respectively. Households who have more livestock holding may not have difficulties purchasing inputs like seed, fertilizer, and the like, and also oxen ownership is among the livestock units considered which help farmers in land preparation and sowing. More livestock ownership also supplies more organic fertilizer to improve both market-oriented cash and stables crops. As the value of livestock holding by the farm household increased by 1%, market-oriented cash and stables crops increased by 4.52% and 4.67% units, respectively. Thus, an increase in livestock holding increases both market orientation indexes of cash and stables crops.

Irrigation users had a positive and significant effect on market-orientated on stables crops at 10%, and more market-orientated on stables crops than non-users; because irrigation user farmers benefit the returns on land and labor are increased, nutrition is improved, and consumption is stabilized as the lean periods are eliminated or reduced. Its benefit is higher yields; higher cropping intensity and all-year-round farm production lead to increased marketable surplus production and perhaps food security. As hypothesized, if the use of irrigation of farm households increased by 1% unit, market-oriented on stables crop found to be increased by 15.89% units.

The educational level of farmers had a positive and significant effect on the market orientation index of cash crops at 5% significant level. As a household head level of education increases by one year of schooling, the household increases the market orientation index of cash crops by 3.62%. This implies that as the educational level of the farmer's increases their ability to get information on how to produce and sell more at the sound market price.

The distance to market and road indicated a negative effect on both market orientation indexes of cash and stables crops. It shows that by maintaining other variables constant when the number of a kilometer to the market increases by one km, the household market orientation index of cash and staples crops declined by 1.23% and 0.95%, respectively; and also it shows that by maintaining other variables constant when the number of a kilometer to the road increases by one km, the household market orientation index of cash and staples crops declined by 0.57% and 0.51%, respectively.

Land cultivated is one of the most important factors of production on which different farm activities were carried out. Land cultivated negatively affects both market orientation indexes of cash and stables crops, and statistically significant at 10% and 5%, respectively. As land cultivated increases by 1.0 ha, market orientation indexes of cash and stables crops decreases by 11.59% and 13.97%, respectively. Thus, farmers might not expand the land cultivated (mean land cultivated was 1.5 ha) for production.

The determinants of crop commercialization

As shown in Table 2, the likelihood function of the Tobit model for crop commercialization index is highly significant (LR Chi2 (25)=95.72 with Prob>Chi2=0.0000) indicating a strong explanatory power of the independent variables. Out of the 25 explanatory variables included in the model, four variables, namely land cultivated, land allocated to staples, irrigation use, and annual total gross income was found to significantly influence crop commercialization.

| Variable | Coefficient | T | P>|t| | Marginal effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | -29.14 | -2.25 | 0.025 | |

| Sex | 4.44 | 0.76 | 0.445 | 2.32 |

| Age | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.805 | 0.03 |

| DeprC | -0.03 | -1.49 | 0.136 | -0.01 |

| Adeq | 1.39 | 1.35 | 0.178 | 0.71 |

| Expr | -0.06 | -0.23 | 0.816 | -0.03 |

| Grade | 0.56 | 0.92 | 0.357 | 0.29 |

| Traing | 1.87 | 0.36 | 0.719 | 0.94 |

| Social | 6.96 | 1.49 | 0.137 | 3.39 |

| Land cultivated | 8.20* | 5.2 | 0 | 4.16 |

| Landst | 0.05** | 1.93 | 0.054 | 0.02 |

| Irrig | 13.85* | 3.11 | 0.002 | 7.58 |

| Fert | 5.46 | 1.03 | 0.302 | 2.68 |

| Govp | 0.39 | 0.06 | 0.949 | 0.2 |

| SWC | -5.24 | -1.19 | 0.235 | -2.72 |

| Hyvc | 4.88 | 1.21 | 0.227 | 2.53 |

| Extcont | -0.02 | -0.78 | 0.436 | -0.01 |

| Lncreditq | -0.0001 | -0.54 | 0.592 | -0.00003 |

| creditR | 1.67 | 0.43 | 0.669 | 0.85 |

| Oxq | -0.31 | -0.11 | 0.913 | -0.16 |

| TLU | 0.51 | 0.74 | 0.458 | 0.26 |

| Market | 0.14 | 1.59 | 0.113 | 0.07 |

| Road | 0.02 | 0.32 | 0.748 | 0.01 |

| Devst | 0.15 | 1.47 | 0.142 | 0.08 |

| Town | 0.0003 | 0.01 | 0.993 | 0.0002 |

| LnOffincom | 0.0006** | 1.83 | 0.068 | 0.0003 |

Note: Number of observations=344; Uncensored obs.=227; Left-censored obs.=116; Right-censored obs.=1; Log likelihood=-1171.1701; Pseudo R2=0.0393; LR chi2 (25)=95.72; Prob>Chi2=0.000.

Land allocated to staples had a positive and significant influence on the level of crop commercialization at 10% probability level of significance. The marginal effect result indicated that as the land allocated to staples by the household increased by one hectare, the decision to participate in crop commercialization would be increased by 2%.

The irrigation user for crop commercialization decision is positive and the effect is statistically significant at 1%. It can lead to a reduction in crop production risk and, therefore, provides greater incentives to increase input use, increase crop yields, intensify crop production and diversify into higher-valued crops. The resulting increase in marketable surplus and commercial activities has the potential to generate increased incomes for farmers. The marginal effect also confirms that the irrigation user increases crop commercialization by 7.58%, all other factors held constant.

The coefficient of land cultivated was positive and statistically significant on crop commercialization at 1% probability level. This could be attributed to the fact that a larger area of arable land provides a greater opportunity to produce a surplus that requires sales. The marginal effect result also indicated that as the land cultivated by the household increased by one hectare, the decision to participate in crop commercialization would be increased by 4.16%. The more the land cultivated, the farmers more participated in crop commercialization.

The coefficient off-farm income was positive and statistically significant crop commercialization at 10% probability level. This is attributed to the fact that off-farm income provides extra capital that is invested in farming in the form of purchasing inputs and hiring labour. Hence, farmers with such earnings reflect higher crop commercialization. The marginal effect result indicated that as the sum of off-farm income of the household increased by one birr the decision to participate in crop commercialization would be increased by 0.03%. This indicates that income from other sources such as trading, wages among others are utilized on the farm to boost production, and to participate in crop commercialization.

The measure of commercialization among respondents

The values of crops produced during the previous cropping season and the amount received for crops sold by respondents were used to determine the commercialization index as shown in Table 3.The mean HCI calculated among the farmers in the study area is 0.23, with a minimum value of 0, a maximum value of 1, and a standard deviation of 0.24. The data indicate that on the commercialization continuum stretching from subsistent to fully commercialized (0-1); many farmers in the study area are situated below the halfway mark at 0.23. Some farmers from the data observed are at 1 while others are at 0, located on the extremes of the commercialization continuum.

| Variable | No. of responses | Mean | Standard deviation | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total value of all crops produced | 344 | 299,426.2 | 28,55,014 | 0 | 5.15e+07 |

| Amount received from all crops sold | 344 | 39,846.90 | 3,73,798 | 0 | 68,53,666 |

| Crop Commercialization Index (CMI) | 344 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0 | 1 |

Note: Source: Computed from Field Survey Data, 2019/20.

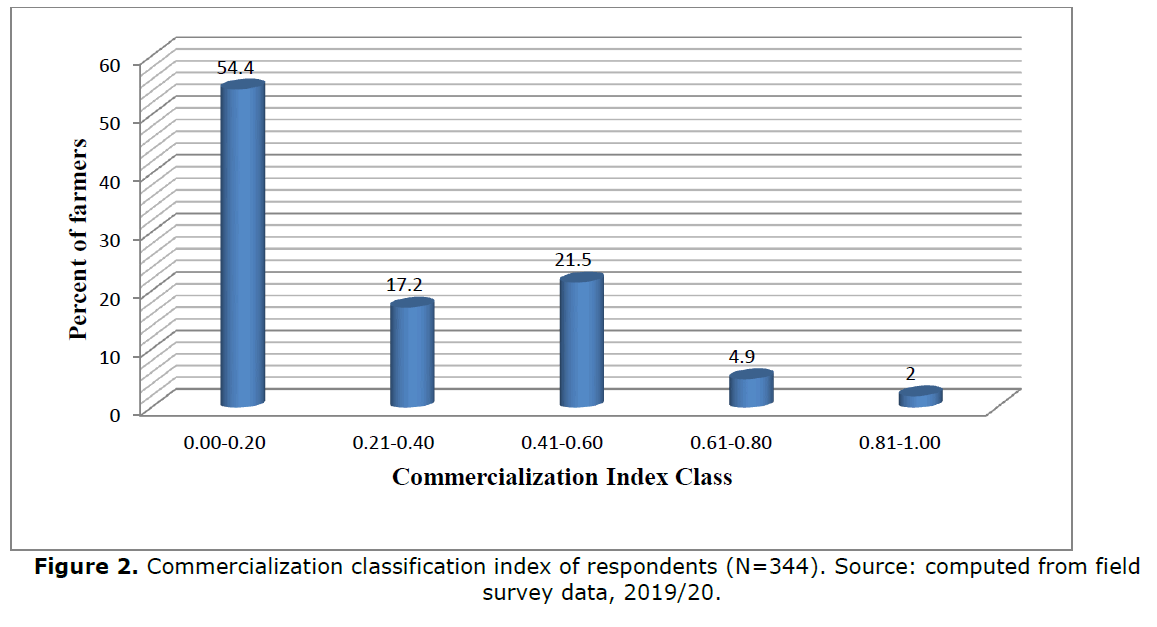

Commercialization classification index

The household commercialization index was used to determine the position of respondents on a commercialization continuum. The continuum was divided into four percentiles and farmers were classified accordingly, as indicated in Figure 2.

As seen from Figure 2, more than 50% of the target population falls into the first percentile of the commercialization index class. Approximately 21.5% of the farmers are in the third percentile of the commercialization index class, and 17.2% of the farmers fall into the second percentile of the commercialization index class. However, close to 2% of the respondents fall in the top percentile of the commercialization index class.

Conclusion and Recommendation

This study aimed to analyse the determinants of market orientation and market participation in Central and North Gondar Rural Ethiopia separately. This study used primary data collected from 344 sampled households through a semi-structured questionnaire. The SUR model estimation indicated that adult equivalent, fertilizer users, and TLU affect both market-oriented cash crops and market-oriented stables crops, while child dependency ratio, land cultivated, the distance to the market, and road affect both markets oriented cash crops and market-oriented stables crops negatively. Levels of education and irrigation users affect market-oriented cash crops and market-oriented stables crops positively, respectively. The Tobit model estimation indicated that land cultivated, land allocated to staples, irrigation users, and off-farm incomes positively affect crop commercialization.

• The education level of the household should up-grade primarily adult education, and building the skill of the household that develop their ability is vital for market orientation.

• Farmers should keep going to employ in additional off-farm income activities for a greater level of crop commercialization.

• The government should improve rural-urban roads in the district as access to village town for market orientation development.

• The child dependency ratio influences market orientation negatively. Farmers with more children (Child dependency ratio) tend to less contribute to market orientation. Therefore, the government is supposed to work strongly on family planning strategy to rural farm households by health extension workers at the kebele level.

• Land cultivated is negatively affected by market-oriented cash crops. So, the farmers must use agricultural intensification derived from production packages like agronomic practices and the proper application of inputs.

• Irrigation users were positively affecting crop commercialization. So, the irrigation administrators should be given more emphasis to improving the irrigation development performance for crop commercialization.

• For the improvement of market orientation, the government should be supplied chemical fertilizer in sufficient amounts and on time at a reasonable price to improve farmers’ crop production.

Acknowledgments

We presented thanks to the University of Gondar for funding and West Belesa, Wogera, and Debark Districts for facilitating data collections and providing data; the farmers who provided the primary data.

Authors’ Contributions

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the University.

References

Holden ST, Otsuka K (2014). The roles of land tenure reforms and land markets in the context of population growth and land use intensification in Africa. Food Policy. 48:88-97. [Crossref] [Google Scholar]Larson DF, Otsuka K, Matsumoto T, Kilic T (2014). Should African rural development strategies depend on smallholder farms? An exploration of the inverse‐productivity hypothesis. Agricultural Economics. 45(3):355-367. [Google Scholar]

Janvry AD, Sadoulet E (2010). Agriculture for development in sub-Saharan Africa: An update. Afric J Agric Res Econom. 5(1):194-204. [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

Fischer E, Qaim M (2012). Gender, agricultural commercialization, and collective action in Kenya. Food security. 4(3):441-453. [Cross ref] [Google Scholar]

Jagwe JN, Machethe CL, Ouma E (2010). Transaction costs and smallholder farmers’ participation in banana markets in the Great Lakes Region of Burundi, Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo. AFJARE. 6 (1):302-317. [Google Scholar]

IFAD (2011). Rural poverty report; International Fund for Agricultural Development.

Pender JL, Alemu D (2007). Determinants of smallholder commercialization of food crops: Theory and evidence from Ethiopia. [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

Olwande J, Smale M, Mathenge MK, Place F, Mithöfer D (2015). Agricultural marketing by smallholders in Kenya: A comparison of maize, kale and dairy. Food policy.52:22-32. [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

Arias P, Hallam D, Krivonos E, Morrison J (2013). Smallholder integration in changing food markets. FAO.[Google Scholar]

Diao X, Hazell P, Thurlow J (2010). The role of agriculture in African development. World devel. 38(10):1375-1383. [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

MoFE, MoARD (2010). Global agriculture and food security program: FYGTP (five-year Growth and Transformation Plan). Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. 41.

Zanello G (2011). Does the use of mobile phone reduce transactions costs and enhance participation in agricultural markets. InHousehold evidence from Northern Ghana, CSAE Conference. [Google Scholar]

Debello MJ, Gardebroek C (2008). Crop and market outlet choice interactions at household level. Eth J Econom. 7(1):29-47. [Google Scholar]

Mamo G, Assefa A, Degnet A (2009). Determinants of smallholder crop farmers’ decision to sell and for whom to sell: Micro-level data evidence from Ethiopia. InProceedings of the Ninth International Conference on the Ethiopian Economy, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. 47-76. [Google Scholar]

Bedaso T, Wondwosen T, Mesfin K (2012). Commercialization of Ethiopian smallholder farmer’s production: Factors and Challenges behind. InPaper presented on the Tenth International Conference on the Ethiopian Economy, Ethiopian Economics Association.19-21. [Google Scholar]

Jaleta M, Gebremedhin B, Hoekstra D (2009). Smallholder commercialization: Processes, determinants and impact. ILRI Discussion Paper. [Google Scholar]

Belesa.

Belesa.