Research Article - (2022) Volume 10, Issue 2

The effect of web-based education programs on self-efficacy and self-care behavior in quality of life among diabetic type 2 patients in public hospital

Tengku Mohd Mizwar Bin T Malek1* and Aini Ahmad22Department of Nursing, KPJ Healthcare University College, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia

Received: 15-Apr-2022, Manuscript No. AERR-22-60961; Editor assigned: 18-Apr-2022, Pre QC No. AERR-22-60961 (PQ); Reviewed: 02-May-2022, QC No. AERR-22-60961; Revised: 09-May-2022, Manuscript No. AERR-22-60961 (R); Published: 19-May-2022, DOI: 10.51268/2736-1853.22.10.061.

Abstract

Aim: This study investigated the intentions, opportunities, and barriers to engaging in a meaningful internationalization of higher education in Malawi, once a global player, to reposition itself on the global stage.

Objective: This study aims to identify the effects of web-based educational programs on Diabetic Self-efficacy Management (DSEM), Diabetic Self-care Behavior Management (DSCM) in Quality of Life (QoL) among type 2 diabetes patients in public hospitals.

Methods: This study used a quantitative quasi-experimental design of pre-test and post-test. Diabetic-N-Care program was conducted at Orthopedic Clinic Hospital Sultana Nur Zahirah Kuala Terengganu for 34 days, where purposive sampling involved type 2 diabetic patients who were divided into intervention groups (IG) (n=60) and control group (CG) (n=60). Respondents are the same individual for each phase of measurement.

Results: Data analysis method the general linear model repeated measures ANOVA, Split-plot ANOVA (SPANOVA) and paired t-test was conducted on 120 patients to see the effect of using Diabetic-N-Care on IG. The results of Split-plot ANOVA analysis showed a significant overall effect of DSEM, DSCM and QoL (p=0.000) on IG. Meanwhile, paired t-test analysis there was a significant mean difference in DSEM, DSCM and QoL at pre-test and post-test (p=0.000) to IG compared to CG.

Conclusion: Web-based health education can have an impact on DSEM, DSCM in the QoL of type 2 diabetic patients where greater than before confidence, change the old behavior to new behavior to improve quality of life in the long term planning. Therefore, this study concludes that web-based methods such as Diabetic-N-Care need to be widely adapted in current health education methods.

Keywords

Web-based, Diabetic self-efficacy management, Diabetic self-care behavior management, Quality of life.

Introduction

The phenomenon of diabetes mellitus is a global challenge today and has reached an alarming level. Several factors have triggered the development of 90% type 2 diabetes and caused metabolic disorders characterized by a variety of complications (Abdullah et al., 2018; Hameed et al., 2015). Based on statistics from The Second National Health and Morbidity Survey, shows that more than 3.4 million Malaysians were diagnosed with diabetes in 2010, which is about 11.8% of the total population in Malaysia, and a dramatic increase of 4.5 million in 2020 (Humaira, 2018). The study from Abdullah et al (2018) and Zanariah et al (2015) believes that apart from the existing factors, cultural practice factors influence this epidemic because of Malaysia’s multi-racial harmony and harmony in terms of customs and culture itself, in addition to the influence of family genetics (Abdullah et al., 2018; Hussein et al., 2015). Cultural food practices that are still practiced, the influence of western food, and food modifications to look more appetizing make an increase in diabetic statistics compared to treatment interventions.

Self-efficacy is considered the most important and key predictor of self-care behavior among type 2 diabetic patients (Lee et al., 2020; Dehghan et al., 2017; Sarkar et al., 2006). The concept of Quality of Life (QoL) related to improved health is increasingly recognized as an important outcome of rehabilitation programs and also as an indicator of how diabetic patients can adapt after a treatment or after discharge from the hospital (Dhatariya et al., 2020). Technology has proven to be a support tool as a medium to conduct key interventions to provide advantages to improve patient health levels and adherence to healthrelated information communicated by the health profession (Zuhaida et al., 2021; Rasoul et al., 2019; Muegge et al., 2016). 21st century patients and healthcare professions need new tools to manage the growing burden of chronic disease (Muegge et al., 2016).

Self-efficacy is able to influence attitudes towards self-care behavior for diabetics but how to convey this concept is still disrupted and need transformation in intervention (Karimy et al., 2018). Meanwhile, education intervention for diabetic patients is inconsistent in controlling glucose levels effectively (Jiang et al., 2019). If seen, health education has traditionally had certain limitations and has caused disconnection between health education and patients. Nevertheless, the absence of long-distance health education guidelines for the treatment of post-discharge disconnection contributes to a poor prognosis. The previous concept of transformation is not enough in health education where there is an increase in the rate of diabetic patients with severe complications. This situation clearly occurs during a natural disaster or COVID-19 pandemic that causes major changes in diabetic life and management. Diabetic patients tend to have various levels of negative emotions, such as depression and anxiety and the effects of this pandemic make them burdened where they have to do diabetic self-management and standard practice of precaution COVID-19 (Banerjee et al., 2020). This situation will affect the effort, suppression, emotion, venting, and wishful thinking in them when in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

This can be clearly seen when clinics are closed for patient rehabilitation, patients are transferred and wards are made COVID-19 patients, and patients start returning home at their own risk for fear of COVID-19 spread in hospitals when treatment is still needed. This condition will worsen in just 7 days if there is no appropriate intervention to help these diabetic patients (Wargny et al., 2021). What can be seen, the traditional educational interventions performed are not sufficient to obtain the desired results because there are no reforms in educational programs such as using theory (Jiang et al., 2019). Diabetic web-based education intervention is a way of selfmanagement that is encouraged in the individual and in turn improves the level of quality of life for a long period of time. The web-based educational intervention program is an innovation and addressing educational problems face-to-face.

This article will briefly highlight some of the key developments in the field of diabetic health education, and how this technology can be integrated into this practice.

Materials and Methods

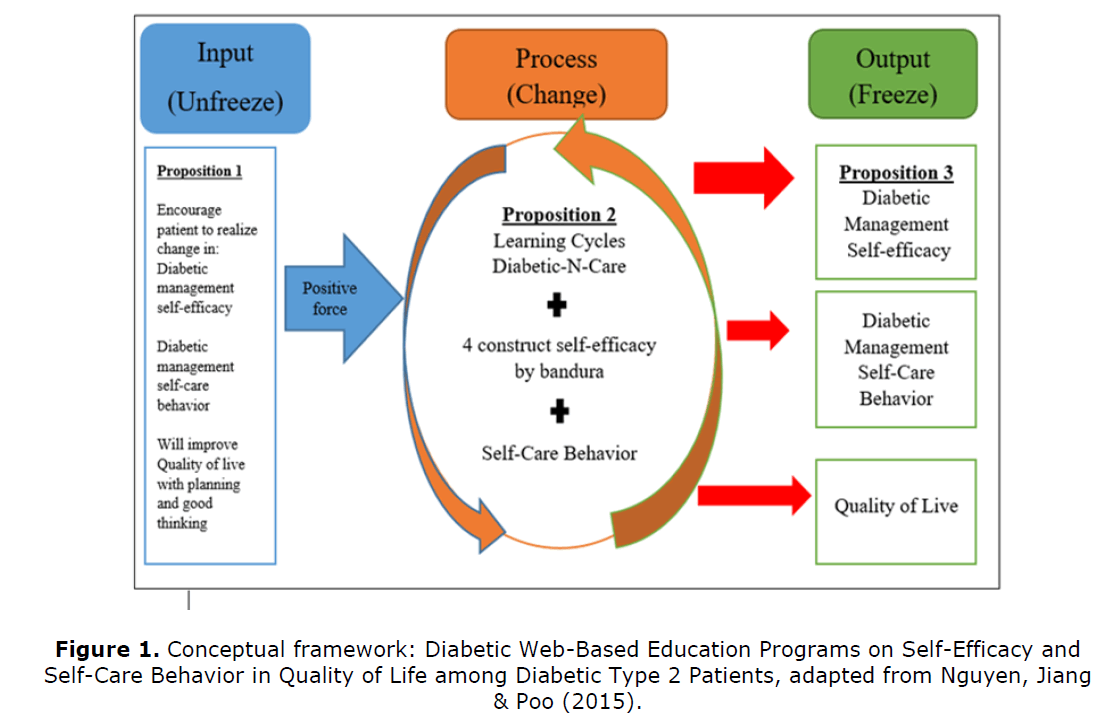

Quantitative quasi-experimental method approach (pre-test and post-test) repeatedmeasures design with intervention and control group. Pre-tests for this study were used to determine whether there were similarities between groups and as a statistical control. Meanwhile, post-test to determine the difference between the intervention group and control group. Both groups received routine diabetes treatment and the intervention group was given health education interventions based on Lewin’s (1947) model of change theory and self-efficacy theory by Bandura (1977) applied in web technology-based diabetes education program interventions (Figure 1).

Population and sampling

The majority of patients were Malay, non - probability purposive sampling techniques were used based on sample size using Raosoft’s online sample calculator (Raosoft Incorporation, 2004). The population size that has been identified is 168 and the recommended sample size is 118 respondents. The sample size for this measure was rounded to 120 respondents for division into intervention (n=60) and control groups (n=60) in this study.

Research instruments

This This instrument was developed by the researcher based on previous studies (Sangruangake et al., 2017; Tharek et al., 2018; John et al., 2019). The questionnaire was translated into Bahasa Melayu, through the back-to-back translation technique. The majority of questionnaires use the Likert Scale 1 to 5 (DSEM; Unsure to Extremely Confident; DSCM; Very Poor to Very Good; QoL; Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree). The results showed for DSEM Cronbach's value α 0.83, DSCM Cronbach's value α 0.93 and QoL Cronbach's value α 0.93. The next process is face validity for relevance issues, comprehensiveness, and clarity, where the researcher has determined 5 professional experts for the review of this study instrument which consists of a research supervisor, orthopedic specialist doctors, head nurse, and two nurses with diabetic post-basic course (Lam et al., 2018; Bonett et al., 2015).

Research procedure

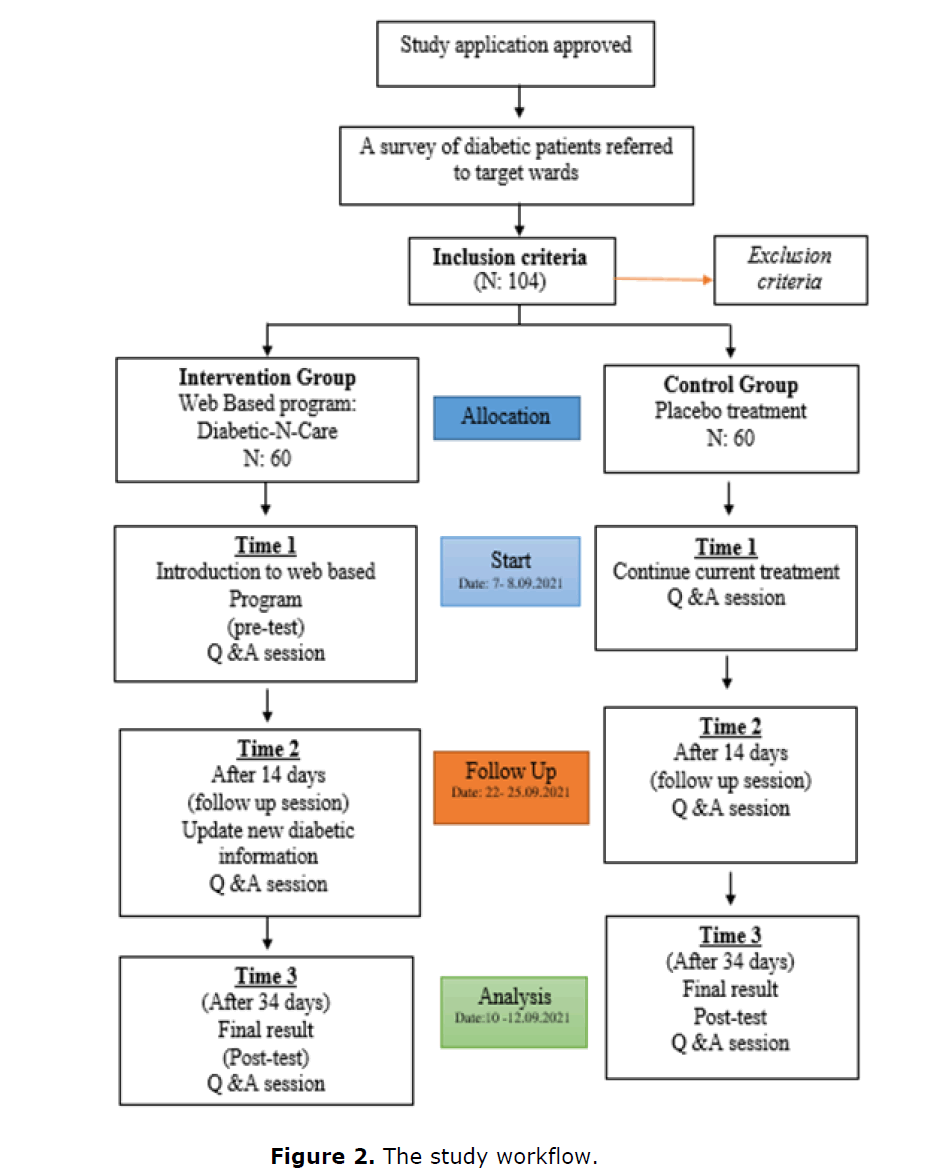

This study is divided into three phases to identify the effect of the use of diabetic education through web-based among respondents. Diabetic-N-Care is a research tool used in educating patients related to diabetic knowledge through web-based. Diabetic-N-Care was formed through the use of Google Sites. The three phases in this research were adapted from the three phases of Kurt Lewin’s theory in addition to using the principles of Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory. Time 1 as a pre-test, Time 2 follow up session after 14 days of the program, and Time 3 final result as a post-test after 34 days of the program (Figure 2). For the selection of inclusion criteria, respondents aged between 20 to 59 years who were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes and no vision and hearing problems. For the exclusion criteria of respondents with a chronic diagnosis and unable to implement the program (e.g. multiple chronic diagnoses e.g. spine and cancer) and type 1 diabetes and pregnant women. While the withdrawal criteria were that respondents could choose to withdraw at any time, the investigator considered it detrimental or risky for the subject to continue, and those who withdrew from the study before entering the follow-up phase would be replaced immediately and through the same process.

Data collection process

Step 1: Implement of material program

After the patient is examined by the doctor, the patient from the intervention group will answer the questionnaire first as a pre-test. After that the researcher will explain the intervention process to the patient. Both groups will respond to the same questionnaire and routine interventions, example: Assessment, health education and treatment by orthopedic doctor and clinic nurses.

Step 2: Education program

The way to access this web is to simply scan the bar code provided as a button badge and patients can see the information related to diabetics provided at any time for reference (Figure 3). After a 2 week of intervention program, the intervention group will receive the latest information via the web related to daily diabetic management. The latest information is based on the lowest scores related to the daily management of diabetics, to increase patient understanding and confidence. Furthermore, IG will also receive orders via what’s App application to log-in and read new information updated by researchers.

Step 3: Evaluation program

After 34 days of the intervention program, this phase is a post-test to evaluate the effect of this program. The researcher was meeting the patient during an appointment date with the specialist to assess the patient’s condition. Patients from the intervention group and the control group were asked to re-answer the same questionnaire. At the final stage of the program, program interventions will be performed on both groups.

Statistical test

After completing the questionnaire by the respondents according to the study phase, the data was then entered into the SPSS-version 25 software. The results were reported in statistical analysis formats such as descriptive statistics (frequency, mean and standard deviation) and inferential statistic. The General Linear Model Repeated Measures ANOVA, Splitplot ANOVA (SPANOVA) and Paired t-test were performed to see the effects and differences to make comparisons between two types of independent variables, one variable consisting of repeated data and interventions on each dependent variable separately in this study. On the other hand, Box’s M and Levene's test were p<0.05 and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test performed showed values from all variables p=0.200, this indicates that the SPANOVA test variance value equality condition has complied. The results of the study indicate that the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test is the best normality test because of its goodness of fit in measuring the fit between the distributions of a series of samples with a specific frequency distribution. The data distribution is positively skewness (Skewness=0.43, Kurtosis=1.92). Data analysis was performed for each phase of the study to see the requirements and weaknesses of respondents through new information to be uploaded in Diabetic-N-Care.

Results

Profile of the sample

The overall demographic data and relates to the clinical characteristics information of respondents for this study (Table 1 and Table 2).

| Variables | Category | Diabetic-N-Care Intervention Group (n:60) | N Missing | Mean S.D | Control Group (n: 60) | N Missing | Mean S.D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 20-25 | 0 (0%) | 0 | 5.883 | 0 (0%) | 0 |

6.317 |

| 30-35 | 8 (13.3%) | 3 (5.0%) | |||||

| 36-39 | 9 (15.0%) | 7 (11.7%) | |||||

| 40-45 | 11 (18.3%) | 12 (20.0%) | |||||

| 46-49 | 6 (10.0%) | 1.8603 | 5 (8.3%) | 1.6312 | |||

| 50-55 | 6 (10.0%) | 12 (20.0%) | |||||

| 56-59 | 20 (33.3%) | 21 (35.0%) | |||||

| Gender | Male | 37 (61.7%) | 0 | 1.383 | 30 (50%) | 0 | 1.5 |

| Female | 23 (38.3%) | 0.4903 | 30 (50%) | 0.502 | |||

| Ethnic | Malay | 58 (96.0%) | 0 | 1.05 | 57 (95%) | 0 | 1.05 |

| Chinese | 3(5.0%) | 3 (5.0%) | |||||

| India | 0 (0%) | 0.2198 | 0 (0%) | 0.2198 | |||

| Other | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |||||

| Education level | Primary | 22 (36.7%) | 0 | 1.75 | 29 (48.3%) | 0 | 1.617 |

| Secondary | 31 (51.7%) | 0.6542 | 25 (41.7%) | 0.6662 | |||

| Tertiary | 7 (11.7%) | - | 6 (10.0%) | ||||

| Occupation status | Employed Unempleyed |

31 (51.7%) | 0 | 1.483 | 15 (25.0%) | 0 | 1.75 |

| 29 (48.3) | 0.5039 | 45 (75.0%) | 0.4367 | ||||

| Marital status | Single | 1 (1.7%) | 0 | 2.05 | 1 (1.7%) | 0 | 2.033 |

| Married | 57 (95.0%) | 57 (95.0%) | |||||

| Widower | 2 (3.3%) | 0.3873 | 1 (1.7%) | 0.3171 | |||

| Widow | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.7%) | |||||

| Total Sample N: 120 | |||||||

| Variables | Category | Frequency (ƒ) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of diabetic (years) | 0-4 | 24 | 20 |

| 9-May | 41 | 34.2 | |

| 14-Oct | 40 | 33.3 | |

| 15+ | 15 | 12.5 | |

| Total | 120 | 100 | |

| Co-morbidities | Hypertension | 52 | 43.3 |

| Heart problem | 23 | 19.2 | |

| Renal problem | 8 | 6.7 | |

| Stroke | 3 | 2.5 | |

| Diabetic treatment management | Diet control | 30 | 25 |

| Oral medication | 52 | 43.3 | |

| Injection insulin | 55 | 45.8 | |

| Other: Traditional | 3 | 2.5 | |

| Smoking status (Male only) | Smoking | 28 | 41.7 |

| Never | 35 | 52.2 | |

| Ex-smoker | 4 | 5.9 | |

| Total | 67 | 100 | |

| Received diabetic education before | Yes | 65 | 54.2 |

| No | 55 | 45.8 | |

| Total | 120 | 100 |

The effect of web-based education programs on self-efficacy and self-care behavior in quality of life among diabetic type 2 patients.

As can be seen in Table 3, shows the data value for descriptive analysis between the intervention and control groups on dependent variables (DSEM, DSCM, and QoL) according to three phases, namely pre-test, follow-up, and post-test for 34 days of this study. Where the data value for each variable showed an increase in the mean value for the pre-test intervention group (44.85 ± 9.92) to post-test (64.13 ± 3.65) for DSEM, DSCM showed pre-test (30.6 ± 6.47) to post-test (39.75 ± 3.43), and QoL showed pre-test (56.91 ± 7.76) to post-test (62.30 ± 2.95). While the mean value for the control group showed recorded data and almost no change. Comparisons between the intervention and control groups using the Paired t-test showed statistically significant differences in the mean scores of each variable for each phase of the study (Table 4).

| Variables | Group | Mean / Std. deviation | N | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre test | Follow-up | Post test | |||

| Self-Efficacy | Intervention | 44.85 | 50.4 | 64.13 | 60 |

| 9.92 | 7.46 | 3.65 | |||

| Control | 51.18 | 50.85 | 50.31 | 60 | |

| 4.33 | 5.08 | 5.05 | |||

| Total | 48.01 | 50.62 | 57.22 | 120 | |

| 8.26 | 6.36 | 8.2 | |||

| Self-Care Behaviour | Intervention | 30.6 | 36.31 | 39.75 | 60 |

| 6.47 | 4.02 | 3.43 | |||

| Control | 26.95 | 28.88 | 28.23 | 60 | |

| 2.91 | 2.7 | 2.72 | |||

| Total | 28.77 | 32.6 | 33.99 | 120 | |

| 5.32 | 5.05 | 6.55 | |||

| Quality of Life | Intervention | 56.91 | 60.53 | 62.3 | 60 |

| 7.76 | 4.51 | 2.95 | |||

| Control | 55.11 | 56.11 | 55.8 | 60 | |

| 3.21 | 3.09 | 3.55 | |||

| Total | 56.01 | 58.32 | 59.05 | 120 | |

| 5.98 | 4.44 | 4.61 |

| Variable | Intervention Group (IG) (n=60) | Control Group (CG) (n=60) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The mean total M±SD | Diff. (Pre-Post) M±SD | Paired t test, p | The mean total M±SD | Diff. (Pre-Post) M±SD | Paired t test, p | |||

| Pre – test | Post – test | Pre – test | Post – test | |||||

| DSEM | 44.8 | 64.1 (3.65) | -19.2 | 0 |

51.7 (5.19) | 50.3 | 1.4 | 0.079 |

| -9.92 | -8.45 | -5.05 | -6.07 | |||||

| DSCM | 30.6 | 39.7 | -9.15 | 0 | 26.9 | 28.23 | -1.28 | 0.001 |

| -6.47 | -3.43 | -4.7 | -2.91 | -2.72 | -2.79 | |||

| QoL | 56.3 | 62.3 | -5.38 | 0 |

55.1 | 55.8 | -0.68 | 0.134 |

| -7.76 | -2.95 | -6.06 | -3.21 | -3.55 | -3.48 | |||

Objective and research questions were answered using inferential statistics the general linear model repeated measures ANOVA, Split-plot ANOVA (SPANOVA) to examine significant differences in mean scores of dependent variables (DSEM, DSCM, and QoL) among type 2 diabetic patients between group’s intervention and control. Presents the SPANOVA results that include Within-subject and Between-subject effects intervention and control groups (Table 5).

| Variable | Sum of squares | df | Mean square | f | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSEM | Within-subject | |||||

| DSEM | 5406.272 | 1.612 | 3353.954 | 167.176 | 0 | |

| DSEM * group | 6441.739 | 1.612 | 3996.339 | 199.195 | 0 | |

| Error(DSEM) | 3815.989 | 190.205 | 20.062 | - | - | |

| Between-subject | ||||||

| Group | 494.678 | 1 | 494.678 | 5.715 | 0.018 | |

| Error | 10214.611 | 118 | 86.565 | |||

| DSCM | Within-subject | |||||

| DSCM | 1751.239 | 1.543 | 1135.241 | 181.793 | 0 | |

| DSCM * group | 928.717 | 1.543 | 602.041 | 96.408 | 0 | |

| Error(DSCM) | 1136.711 | 182.029 | 6.245 | |||

| Between-subject | ||||||

| Group | 5107.6 | 1 | 5107.6 | 138.243 | 0 | |

| Error | 4359.689 | 118 | 36.947 | |||

| QoL | Within-subject | |||||

| QoL | 602.206 | 1.372 | 439.019 | 41.146 | 0 | |

| QoL * group | 332.772 | 1.372 | 242.597 | 22.737 | 0 | |

| Error(QoL) | 1727.022 | 161.862 | 10.67 | |||

| Between-subject | ||||||

| Group | 1617.136 | 1 | 1617.136 | 34.878 | 0 | |

| Error | 5471.061 | 118 | 46.365 | |||

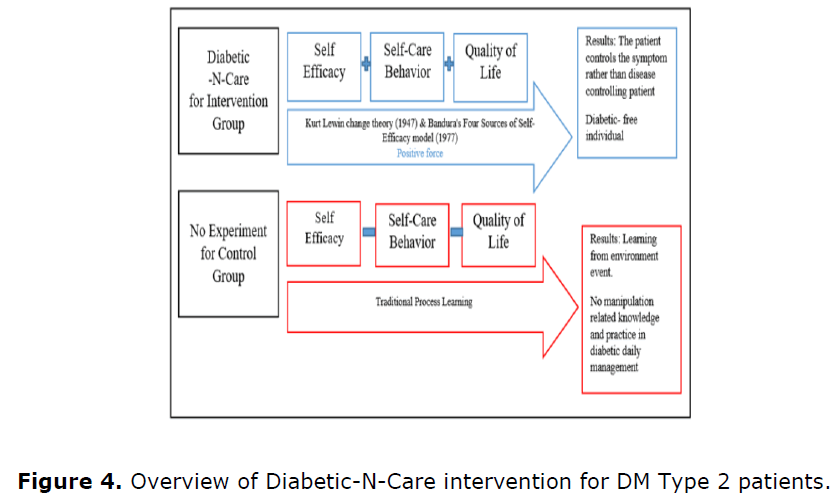

Overall the results through inferential analysis showed significant differences, and alternative hypotheses were accepted. Where researchers have confirmed there are significant differences in web-based educational programs on selfefficacy and self-care behaviors in improving quality of life among type 2 diabetes patients in this study. Figure 4 shows as an in one piece how the process of this study has been carried out and has shown the level of health that can be improved.

Discussion

This study is an intervention in conveying diabetic daily treatment modification information and also as a moderator to confidence for action during limited movement of patients to seek counseling such as the last COVID-19 pandemic situation. This situation is necessary in identifying and revealing that the danger is if the patient only has the knowledge but not the element of confidence in performing management actions. The situation and variety of diabetic complications cause patients to become increasingly less confident and environmental situations to be less helpful. The results of this study are reinforced by the use of two theories, Kurt Lewin change theory (1947) and Bandura's Four Sources of Self-Efficacy model (1977) are elements of knowledge transfer and change to diabetic type 2 patients by able to influence the choice, and related behavior change to perform and reduce stress levels and lower risk of depression than those with low self -efficacy (Hood et al., 2015).

The findings of this study have reported that web-based interventions through Diabetic-NCare are significantly effective on DSEM, DSCM and QoL changes among type 2 diabetic patients. The key in management is enhanced confidence and this confidence needs to be applied in management correct diabetics from interventions from professionals (Abedini et al., 2020; Hurst et al., 2020). DSEM is an indicator of a better quality of life (Rasoul et al., 2019). This study is a learning approach known as ‘mobile alert’ to DSCM from IG after DSEM is enhanced. The findings of this study are a clear source of data because of the data collection process, the findings of the measured analysis and the implementation of the program for 34 days during the MCO, where the face-to-face paralysis of the health education system is widespread. This is a picture of research in real situations is a reality data. Based on Kurt Lewin change theory (1947) and Bandura's Four Sources of Self-efficacy model (1977), a presentation can be implemented effectively and comprehensively especially in providing new knowledge and practices such as food label reading, influence control, glucometer machine reading when exit and more effective medication management. This learning cycle has also had an impact on improving quality of life in accepting health levels and trying to change to a more comfortable and productive lifestyle. While the effect on QoL, self-efficacy interventions are able to influence behavior in improving quality of life through more effective chronic disease management in looking at health outcomes and making comparisons (Peters et al., 2019; Sinha et al., 2011).

However, researchers have detected some difficulties in changing the domain of physical activity and glucose management through glucose inspection before food intake and carrying a glucometer machine when going out is very low for DSCM. Once DSEM is enhanced, patients need to adapt to DSCM (Yee et al., 2018). This cycle is important because it affects 50% of diabetic complications from unbalanced practices (Karimy et al., 2018; Yee et al., 2018). The results of subscale analysis of the physical activity domain still require an increase in the diversity of interventions and unbalanced dietary pattern intake is still consistent with a significant increase in diabetic cases (Banerjee et al., 2020; Kuan et al., 2021). In addition, researchers have detected a financial factor concern in failure and continuing treatment and self -management among diabetic patients. This is in line with the findings of the studies of Raghavendran, Inbaraj & Norman (2020), Cefalu et al (2018) and Campbell et al (2017) where this issue is increasingly worrisome for each consecutive year (Raghavendran et al., 2020; Cefalu et al., 2018; Campbell et al., 2017).

Implication

Through the development of industry 4.0 technology and widespread acceptance among the community has given a privilege in the development of health education strategies. This study has given a new breath in webbased health education among type 2 diabetic patients at HSNZ Kuala Terengganu (danAnalisis, 2018). The disconnection and treatment process when the patient is discharged from the ward is a matter that needs to be taken into consideration because the period of follow -up treatment at the health clinic takes a long time. This web-based is a medium for patients to enhance and do reflection for each health education delivered in the ward when environmental factors and personal factors are not helpful.

Continuing health education can provide a positive impact and diversify intervention strategies from the health profession itself can form a more complete treatment cycle. Through web-based education, Diabetic-N-Care has given patients a privilege in browsing information resources related to daily diabetic management and facilitated health educators such as nurses who always think about what patients will do after discharge from the ward. This situation has provided a privilege and facility to reduce the burden from various parties.

Limitation of the Study

This study was only conducted at the orthopedic clinic, HSNZ Kuala Terengganu which only involved one hospital and clinic. This is because the number of type 2 diabetic patients can be placed in any ward such as general surgical ward and diabetic resource center as outpatients. The limited population and sample during the data collection process of this study is the compliance with the SOP to COVID-19 at that time by the hospital and the head of department.

Conclusion

For this quantitative quasi-experimental study, it has been proven that the web-based Diabetic-N-Care diabetic education intervention has an effect on the variables of this study namely DSEM, DCM and QoL for type 2 diabetic patients of 60 people for IG.

Throughout this study there were no side effects experienced by the patient such as malpractice or death. Statistically significant effects have shown better improvement when compared to traditional learning such as face to face, oral methods, and current experience. The results of this study have given a new breath to educational and learning interventions related to the management of daily diabetics and diabetic patients where greater than before, change the old behaviour to new behaviour to improve quality of life in the long term planning. Therefore, this study concludes that web-based methods such as Diabetic-NCare need to be widely adapted in current health education methods.

Recommendation

Findings from the study can be suggested by involving the psychological management of status among type 2 diabetic patients especially among newly diagnosed patients. Here what can be seen, newly diagnosed patients are somewhat marginalized perhaps because they have only one diagnosis or the progress of diagnosis treatment is still stable. Acceptance of disease diagnosis at a young age and career can disrupt the level of psychology that disrupts individual function to the community.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Funding

Self-funding

Acknowledgment

The study was conducted according to guidelines and approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of the Ministry of Health Malaysia (MREC) (NMRR- NMRR-21- 1446-59624/KKM/NIHSEC/P21-1403, approval date: 9 September 2021).

This study did not receive funding from any institutions.

References

Abdullah N, Abdul Murad NA, Attia J, Oldmeadow C, Kamaruddin MA, Abd Jalal N, Ismail N, Jamal R, Scott RJ, Holliday EG (2018). Differing contributions of classical risk factors to type 2 diabetes in multi-ethnic Malaysian populations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 15(12):pp:2813. [Cross Ref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

Abedini MR, Bijari B, Miri Z, Shakhs Emampour F, Abbasi A (2020). The quality of life of the patients with diabetes type 2 using EQ-5D-5 L in Birjand. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 18(1):1-9. [Cross Ref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

Banerjee M, Chakraborty S, Pal R (2020). Diabetes self-management amid COVID-19 pandemic. Diabetes Metab. Syndr: Clin. Res. Rev. 14(4):351-354. [Cross Ref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

Bonett DG, Wright TA (2015). Cronbach's alpha reliability: Interval estimation, hypothesis testing, and sample size planning. J. Organ. Behav. 36(1):3-15. [Cross Ref] [Google Scholar]

Campbell DJ, Manns BJ, Hemmelgarn BR, Sanmartin C, Edwards A, King-Shier K (2017). Understanding financial barriers to care in patients with diabetes: An exploratory qualitative study. Diabetes Educ. 43(1):78-86. [Cross Ref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

Cefalu WT, Dawes DE, Gavlak G, Goldman D, Herman WH, Van Nuys K, Powers AC, Taylor SI, Yatvin AL (2018). Insulin access and affordability working group: Conclusions and recommendations. Diabetes. Care. 41(6):1299-1311. [Cross Ref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

Dan Analisis JP (2018). Awareness of diabetes mellitus among public attending the primary health centres in malaysia. JQMA. 14(2):11-23. [Google Scholar]

Dehghan H, Charkazi A, Kouchaki GM, Zadeh BP, Dehghan BA, Matlabi M, Mansourian M, Qorbani M, Safari O, Pashaei T, Mehr BR (2017). General self-efficacy and diabetes management self-efficacy of diabetic patients referred to diabetes clinic of Aq Qala, North of Iran. J. Diabetes. Metab. Disord. 16(1):1-5. [Cross Ref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

Dhatariya K, Corsino L, Umpierrez GE (2020). Management of diabetes and hyperglycemia in hospitalized patients. Endotext [Internet]. [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

Hameed I, Masoodi SR, Mir SA, Nabi M, Ghazanfar K, Ganai BA (2015). Type 2 diabetes mellitus: From a metabolic disorder to an inflammatory condition. World. J. Diabetes. 6(4):598-612. [Cross Ref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

Hood KK, Hilliard M, Piatt G, Ievers-Landis CE (2015). Effective strategies for encouraging behavior change in people with diabetes. Diabetes. Manag. (Lond). 5(6):499-510. [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

Hurst CP, Rakkapao N, Hay K (2020). Impact of diabetes self-management, diabetes management self-efficacy and diabetes knowledge on glycemic control in people with Type 2 Diabetes (T2D): A multi-center study in Thailand. PLoS. One. 15(12):e0244692. [Cross Ref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

Hussein Z, Taher SW, Singh HK, Swee WC (2015). Diabetes care in Malaysia: Problems, new models, and solutions. Ann. Glob. Health. 81(6):851-862. [Cross Ref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

Jiang X, Wang J, Lu Y, Jiang H, Li M (2019). Self-efficacy-focused education in persons with diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 12:67-79. [Cross Ref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

John R, Pise S, Chaudhari L, Deshpande PR (2019). Evaluation of quality of life in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients using quality of life instrument for Indian diabetic patients: A cross-sectional study. J. Mid-Life Health. 10(2):81. [Cross Ref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

Karimy M, Koohestani HR, Araban M (2018). The association between attitude, self-efficacy, and social support and adherence to diabetes self-care behavior. Diabetol. metab. syndr. 10(1):1-6. [Cross Ref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

Kuan YC, Tong CV, Katiman E, Tiong XT, Chan PL, Tan F, Noor NM (2021). Effects of Movement Control Order (MCO) During Covid-19 Pandemic on Patients with Diabetes Mellitus (DM) in Malaysian Tertiary Centers. J. Endocr. Soc. 5(Supplement_1):A339-A340. [Cross Ref] [Google Scholar]

Lam KW, Hassan A, Sulaiman T, Kamarudin N (2018). Evaluating the face and content validity of an instructional technology competency instrument for university lecturers in Malaysia. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences. 8(5):367-385. [Cross Ref] [Google Scholar]

Lee J, Lee EH, Chae D (2020). Self‐efficacy instruments for type 2 diabetes self‐care: A systematic review of measurement properties. J. Adv. Nurs. 76(8):2046-2059. [Cross Ref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

Muegge BD, Tobin GS (2016). Improving diabetes care with technology and information management. Mo Med. 113(5):367-371. [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

Peters M, Potter CM, Kelly L, Fitzpatrick R (2019). Self-efficacy and health-related quality of life: a cross-sectional study of primary care patients with multi-morbidity. Health. Qual. Life Outcomes. 17(1):1-1. [Cross Ref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

Raghavendran S, Inbaraj LR, Norman G (2020). Reason for refusal of insulin therapy among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in primary care clinic in Bangalore. J. Family. Med. Prim. Care. 9(2):854. [Cross Ref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

Raosoft Incorporation (2004). Raosoft Sample Size Online Calculator. (Internet) c2004.

Rasoul AM, Jalali R, Abdi A, Salari N, Rahimi M, Mohammadi M (2019). The effect of self-management education through weblogs on the quality of life of diabetic patients. BMC Medical. Inform. Decis. Mak. 19(1):1-2. [Cross Ref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

Sangruangake M, Jirapornkul C, Hurst C (2017). Psychometric properties of diabetes management self-efficacy in Thai type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: A multicenter study. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2017: 2503156. [Cross Ref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

Sarkar U, Fisher L, Schillinger D (2006). Is self-efficacy associated with diabetes self-management across race/ethnicity and health literacy?. Diabetes Care. 29(4):823-829. [Cross Ref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

Sinha R, van den Heuvel WJ, Arokiasamy P (2011). Factors affecting quality of life in lower limb amputees. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 35(1):90-96. [Cross Ref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

Tharek Z, Ramli AS, Whitford DL, Ismail Z, Mohd Zulkifli M, Ahmad Sharoni SK, Shafie AA, Jayaraman T (2018). Relationship between self-efficacy, self-care behaviour and glycaemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in the Malaysian primary care setting. BMC Fam. Pract. 19(1):1-0. [Cross Ref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

Wargny M, Potier L, Gourdy P, Pichelin M, Amadou C, Benhamou PY, Bonnet JB, Bordier L, Bourron O, Chaumeil C, Chevalier N (2021). Predictors of hospital discharge and mortality in patients with diabetes and COVID-19: Updated results from the nationwide CORONADO study. Diabetologia. 64(4):778-794. [Cross Ref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

Yee KC, Md Said S, Abdul Manaf R (2018). Identifying self-care behavior and its predictors among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients at a district of Northern Peninsular Malaysia. Mal. J. Med. Health. Sci. 14(2):17-29. [Google Scholar]

Zuhaida HS, Chung HC, Said FM, Tumingan K, Shah NS, Hanim S, Bakar A (2021). The Best Online Tools Based on Media Preference Reflected by Health Information Received on Social Media amongst Diabetic Patients in Hospital Canselor Tuanku Muhriz, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Malays. J. Med Sci. 28(3):118-128. [Cross Ref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]